Google Explores Space-Based AI with 81-Satellite Solar Clusters

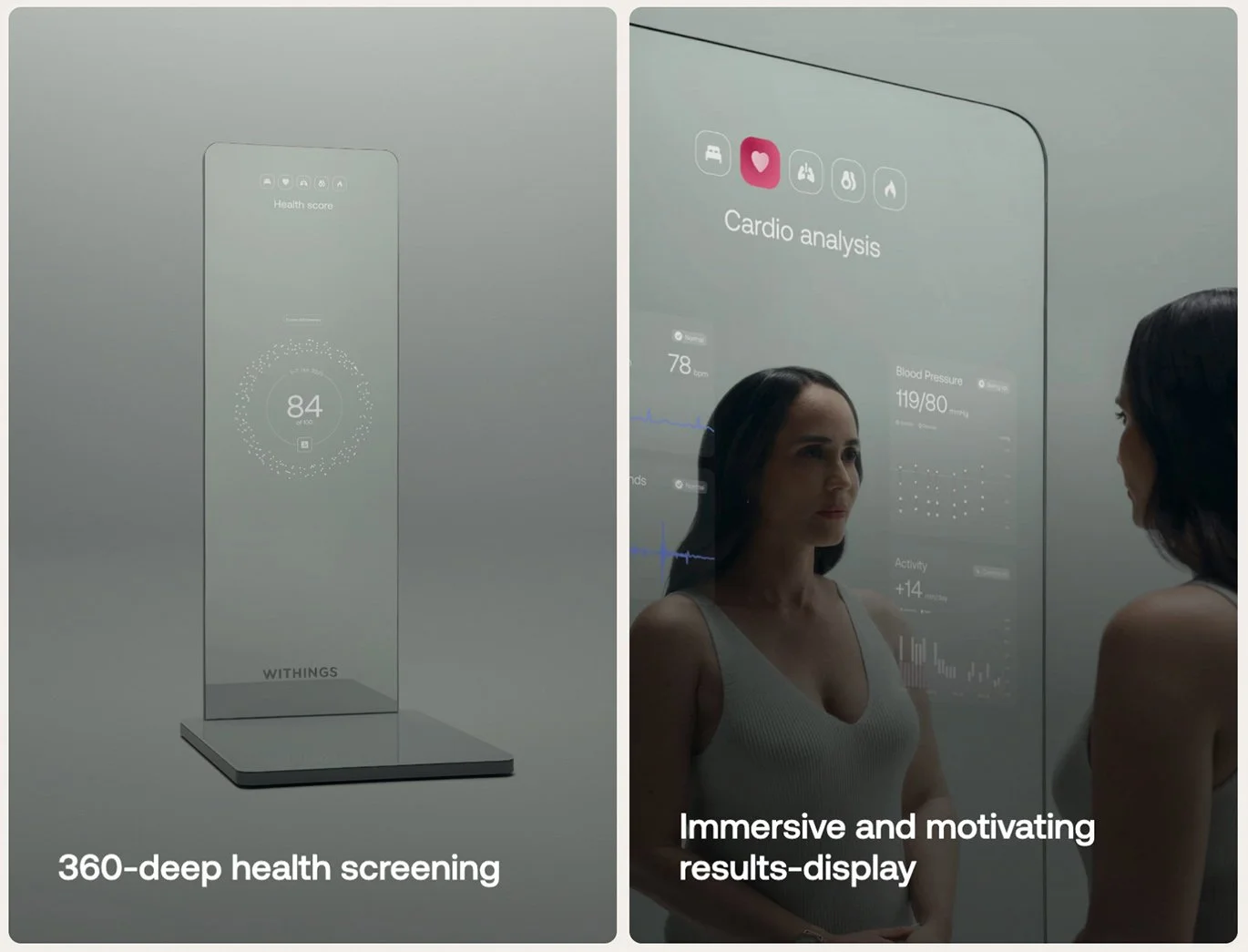

AI-generated Image for Illustration Only (Credit: Jacky Lee)

Google is exploring whether future generations of artificial intelligence (AI) systems could be trained and run in space, where near-continuous sunlight and vacuum conditions might ease the growing strain on terrestrial power grids.

The effort, known as Project Suncatcher, was publicly unveiled in early November 2025 via a Google Research blog post and a technical preprint titled “Towards a future space-based, highly scalable AI infrastructure system design”.

The concept calls for clusters of small satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO), each equipped with Google’s custom Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), operating as a distributed AI data centre powered almost entirely by solar energy.

The preprint describes Suncatcher as an early, research-stage exploration rather than a deployment roadmap. It outlines a long-term vision in which space-based compute could become cost-competitive with terrestrial data centres if launch prices fall substantially over the next decade.

AI and Energy Constraints on Earth

Google’s work is framed against rapidly rising energy demand from AI workloads. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that data centres, data transmission networks and cryptocurrencies together consumed around 2% of global electricity use in 2022, with data centres alone accounting for roughly 1–1.5%, and demand is expected to grow sharply as AI models scale.

In the United States, several analyses now project that data centres could consume around 8–9% of U.S. electricity by 2030, up from roughly 3% in 2022, if present trends continue and if new AI-heavy facilities proceed as planned.

Conventional data centres also face local constraints:

Grid and siting tension: Regions such as Northern Virginia and parts of Europe have seen planning friction over grid capacity, land use and noise.

Water use: Many facilities rely on evaporative cooling, which draws on local freshwater resources; studies and reporting have raised concerns about water stress in some markets.

Space-based solar power has long been discussed as a way to circumvent intermittency. In the Suncatcher paper, Google’s researchers note that satellites in sun-synchronous LEO at around 650 km can receive sunlight for the vast majority of each orbit, avoiding night-time and most weather interruptions that limit ground-based solar.

Their calculations suggest that, given continuous illumination and optimised panel orientation, solar arrays in such orbits could collect up to roughly eight times more solar energy per year than comparable ground installations at mid-latitudes, although this advantage must be weighed against launch costs and orbital constraints.

How Project Suncatcher Would Work

Satellite Constellation Design

In its illustrative design, Suncatcher uses clusters of 81 satellites flying in a tight formation in a sun-synchronous orbit at approximately 650 km altitude.

Key parameters in the paper’s reference configuration include:

Cluster radius: about 1 km

Inter-satellite spacing: nearest-neighbour distances oscillating between roughly 100 and 200 metres during an orbit due to orbital dynamics

Orbit type: dawn-to-dusk sun-synchronous LEO, keeping the cluster in near-continuous sunlight for power generation

Formation-flying simulations in the paper suggest that such a configuration can be kept stable with modest station-keeping manoeuvres, accounting for Earth’s oblateness (J2 perturbation) and other effects.

Optical Links as “Cables” in Space

Rather than physical cabling, Suncatcher relies on free-space optical inter-satellite links (OISLs) to connect the satellites into a single logical compute cluster.

Laboratory tests described in the preprint, using off-the-shelf components, demonstrated 800 Gbps one-way (1.6 Tbps bidirectional) transmission over a short free-space path.

The design envisages:

Dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) with up to 24 channels on a 100 GHz grid, for 9.6 Tbps bidirectional bandwidth per optical aperture, and potentially 12.8 Tbps with tighter channel spacing.

Spatial multiplexing at shorter distances, where multiple beams from small telescopes are combined to scale total throughput as satellites fly closer together.

Together, the architecture aims to approximate the aggregate bandwidth of high-end terrestrial data-centre networks, but using line-of-sight laser links instead of fibre.

Radiation Testing of TPUs

One of the key technical questions is whether modern, high-density AI accelerators can survive the radiation environment of LEO.

The Suncatcher paper reports tests of Google’s V6e Trillium Cloud TPU and its associated host system in a 67 MeV proton beam at UC Davis’s Crocker Nuclear Laboratory, designed to emulate conditions in sun-synchronous LEO with about 10 mm aluminium-equivalent shielding.

Findings include:

The expected total ionising dose (TID) over five years in the target orbit is about 750 rad(Si).

High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) on the TPU showed irregularities at around 2 krad(Si), nearly three times that five-year requirement, but the TPU logic and end-to-end machine-learning workloads continued to operate correctly up to 15 krad(Si), the maximum tested dose.

Single-event effects (SEEs) are present but appear manageable for inference workloads using error-correcting codes and other mitigations; training workloads will require further study.

These results suggest that, with appropriate shielding and system-level safeguards, TPUs could survive multi-year missions in LEO, though operational error-handling will be critical.

Launch Economics and Power Cost

A major section of the preprint examines whether the cost of launching such constellations could become comparable to terrestrial power costs.

The authors analyse public data on SpaceX’s launch history and project that, if learning-curve trends continue and fully reusable systems such as Starship reach high launch cadence, LEO launch prices around USD 200 per kilogram by the mid-2030s are plausible, though not guaranteed.

Using several existing LEO satellite designs as benchmarks, they estimate that at USD 200/kg, the annualised “launched power price” (cost per kilowatt per year of orbital power capacity) could fall in the USD 810–7,500 per kW-year range, overlapping with the USD 570–3,000 per kW-year range for current U.S. data-centre electricity spend.

The paper stresses that this is a high-level, indicative comparison and not a full economic feasibility study. Ground infrastructure costs, chip costs and operational complexities in space are not fully itemised.

Industrial Partners and Prototype Plans

Google’s blog post notes that the company plans to launch two prototype satellites by early 2027 in partnership with Planet Labs, a commercial Earth-imaging company whose spacecraft bus designs are being adapted for Suncatcher.

The prototypes are expected to test:

Solar-power generation and thermal management in the target orbit

Operation of TPUs in space, building on the radiation tests

Early versions of high-bandwidth optical inter-satellite and satellite-to-ground communication

The precise number of TPUs per prototype satellite, and detailed on-orbit workloads, have not been disclosed publicly as of December 2025.

What Suncatcher Does Not Solve Yet

Despite the ambitious long-term framing, Project Suncatcher does not address current AI capacity bottlenecks:

The first in-orbit tests are scheduled for 2027, and large operational clusters, if they ever materialise, are likely many years beyond that.

Ground-based sites, including new nuclear, geothermal and grid-connected solar projects, remain the primary focus for handling near-term AI growth at Google and elsewhere.

There are also structural limitations:

Latency: Signals between Earth and LEO typically add tens of milliseconds each way. While acceptable for some workloads, this is slower than terrestrial fibre for highly latency-sensitive applications.

Servicing and reliability: The paper itself notes that failed accelerators are easily swapped in Earth data centres, but in space they would either require redundancy (over-provisioning) or new robotic-repair approaches, both of which add cost and complexity.

Debris and safety: Any large constellation must contend with space-debris mitigation, collision avoidance and regulatory approvals for the use of orbital slots, though Suncatcher is still at the research stage and not yet a licensed system.

A Crowded Field: Other Orbital Compute Experiments

Google is not alone in exploring AI compute in space.

Starcloud / Lumen and the H100 “Data Centre in Orbit”

On 2 November 2025, a SpaceX Falcon 9 Bandwagon rideshare mission carried a CubeSat named Starcloud-1, a technology-demonstration spacecraft described as an on-orbit AI compute node featuring an NVIDIA processor intended to run large language models in space.

Satellite tracking databases list the spacecraft as STARCLOUD-1 / LUMEN-1, indicating that the company now operates under the Lumen brand while retaining the Starcloud heritage.

Starcloud/Lumen’s concept emphasises:

A single small satellite with high-performance GPU-class compute

Demonstrating inference and data-processing workloads in orbit

Exploring potential power and cost savings from uninterrupted orbital solar power

Public materials from the company describe energy-cost reductions of up to an order of magnitude compared with some terrestrial data centres, though these figures are scenario-dependent and not independently verified.

Musk, Bezos and Space-Based Data Centres

The idea of running data centres in space has also been endorsed, at least rhetorically, by major space-industry figures:

Elon Musk recently commented that SpaceX “will be doing” data centres in space, in response to online discussion of orbital compute concepts.

Jeff Bezos has for years argued that heavy industry should eventually move off-planet, and in 2025 public remarks he suggested that very large orbital data centres could become viable within a decade or two as launch costs fall.

These statements, while not detailed technical plans, underline growing interest among launch providers in hosting compute or power infrastructure in orbit.

Other Space Solar Power Experiments

The Caltech Space Solar Power Demonstrator (SSPD-1), launched in 2023, has already tested key elements of space-to-Earth power beaming from a small prototype, showing that usable power can be transmitted wirelessly from orbit, albeit at low efficiency and modest scale.

While Suncatcher focuses on using solar power directly for on-orbit compute rather than beaming energy to Earth, it builds on similar physical principles.

How Plausible Is the Economics?

The central economic thesis of Suncatcher is that if launch costs fall dramatically and if satellite designs can be optimised for high watts per kilogram, orbital power for compute could approach the cost of grid electricity plus data-centre overhead on Earth.

The paper’s own caveats are substantial:

Launch cost projections to USD 200/kg or below rely on continued high learning rates and very large cumulative mass launched by vehicles such as Starship.

The analysis looks primarily at power cost, not at full lifecycle costs including satellite manufacturing, complex ground stations, insurance, deorbiting, and the premium that would likely apply to high-reliability space hardware.

Terrestrial energy prices are regionally varied and could change over the project’s multi-decade horizon, particularly as more renewables and grid-scale storage come online.

In other words, Suncatcher is framed as a forward-looking research line, not as evidence that orbital AI is already competitive or imminent.

Outlook: Research Testbed, Not Immediate Grid Relief

As of December 2025, Project Suncatcher is best understood as:

A research testbed for formation-flying, optical networking, thermal management and radiation-hardened AI accelerators in space;

A scenario analysis for when, and under what conditions, space-based compute might become economically viable; and

A signal that large AI developers are exploring unconventional infrastructure options in response to mounting energy, grid and siting challenges on the ground

The first meaningful data on Suncatcher will likely come from the 2027 prototype launches with Planet Labs. Until then, terrestrial data centres, augmented by new clean-energy projects and efficiency improvements, remain the backbone of AI infrastructure.

Whether orbital compute eventually becomes a mainstream option will depend less on physics, which the Suncatcher paper argues is favourable, and more on economics, regulation and long-term reliability in a crowded and contested low Earth orbit.

We are a leading AI-focused digital news platform, combining AI-generated reporting with human editorial oversight. By aggregating and synthesizing the latest developments in AI — spanning innovation, technology, ethics, policy and business — we deliver timely, accurate and thought-provoking content.